Government Involvement in Catastrophe Insurance Markets

The difficulties faced by insurance markets in financing catastrophic risk have given rise to pressures for government to become involved in the market. Government involvement usually occurs when there has been a major failure in private insurance markets.

In the United States, the federal government provides subsidized flood insurance; and the current markets for hurricane coverage in Florida and earthquake insurance in California exist largely due to state government intervention.

By adopting TRIA, the U.S. government intervened to create a market for terrorism insurance. Governments of several other industrialized countries have also intervened in the markets for catastrophe insurance.

This section provides a review of the principal government programs for catastrophe insurance. Because these programs are subject to book-length treatment elsewhere (e.g., Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2005a,b), the discussion of program characteristics is brief. The discussion also emphasizes the programs adopted in the United States.

Federal Flood Insurance

In the United States, the federal government provides flood insurance through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

The flood program was enacted in 1968 in response to a market failure in the private flood insurance market, where floods were generally viewed as uninsurable because of the concentration of risk in specific areas and the resulting potential for catastrophes (Moss, 1999).

Flood insurance was viewed from a policy perspective as a way to prefund disaster relief and provide incentives for risk mitigation. This type of insurance is important because homeowners insurance and other types of property insurance policies exclude coverage for floods.

NFIP flood insurance policies are offered at prices that are subsidized for many buyers and are sold through private insurers, although the federal government bears the risk. The program was designed to be self-supporting and has the ability to borrow from the government to pay claims.

The stated objectives of the program are (i) to provide flood insurance coverage to a high proportion of property owners who would benefit from such coverage, (ii) to reduce taxpayer-funded disaster assistance resulting from floods, and (iii) to reduce flood damage through flood-plain management and enforcement of building standards (Jenkins, 2006).

By August 2005, Jenkins (2006) estimated that the NFIP had approximately 4.6 million policyholders in 20,000 communities. From 1968 through August of 2005, the NFIP had paid $14.6 billion in insurance claims, primarily funded by policyholder premium payments.

Although the program might seem to be a success (in terms of the amount of coverage provided and claims that have been paid), in fact, the NFIP is badly in need of reform.

The program is not actuarially sound, with some policyholders paying premiums representing only 35 to 40 percent of expected costs (Jenkins, 2006).

Following the record losses from hurricanes in 2004 and 2005, the program is currently bankrupt and could not continue to exist in its present state if it were a private insurer.

Moreover, the program pays significant amounts of money to repair or replace “repetitive-loss properties;” that is, properties that receive loss payments of $1,000 or more at least twice over a 10-year period.

It is estimated that such properties, which represent only 1 percent of covered properties, account for 25 to 30 percent of all loss payments (Jenkins, 2006). Insurance penetration rates are low, even in the most flood-prone areas, with as little as 50 percent of exposed properties covered by insurance.

In Orleans Parish, which includes New Orleans, only about 40 percent of properties were covered by flood insurance at the time Katrina struck (Bayot, 2005) and coverage rates were even lower in parts of Mississippi.

The NFIP also has been criticized for not providing effective oversight of the approximately 100 insurance companies and thousands of insurance agents and claims adjusters who participate in the flood program (Jenkins, 2006).

Reforming the NFIP should become a top priority for federal disaster planning. Having high rates of flood insurance coverage can significantly reduce taxpayer-funded disaster-relief payments following catastrophes, and charging actuarially sound premiums would provide proper incentives for flood-plain management.

There are two approaches that could be taken to reforming the program: (i) Continue providing federal flood insurance but fix the problems with the current program.

This would entail charging premiums sufficient to cover both claims and program expenses and providing a safety cushion to build up reserves during low-loss years to reduce the need for federal borrowing during years when catastrophes occur.

Further, other problems identified by the GAO would also need to be rectified. (ii) Adopt a solution with a higher degree of private sector involvement.

This could be done following the pattern of the federal terrorism program by requiring private insurers to “make available” private flood insurance policies at actuarially determined prices in flood-prone areas.

Although it is probable that private insurers could provide such coverage without federal support, by issuing disaster bonds (similar to CAT bonds) and through conventional reinsurance solutions, consideration should be given to providing federal reinsurance at prices that would be self-supporting in the long run.

The private sector solution is attractive for a number of reasons, including the relative efficiency of insurers in settling insurance claims in comparison with the often chaotic federal response to disaster relief.

Under either solution to NFIP reform, rules should be tightened to eliminate repetitive-loss properties from the program, and lenders should be required to enforce mandatory participation in the program as a condition for granting and retaining mortgage loans, as is presently done for homeowners insurance.

Windstorm Coverage in California and Florida. Windstorm coverage is presently provided by private insurers through homeowners and other property insurance policies.

The California and Florida programs are noteworthy in that they do not involve the direct government provision of insurance but the creation of quasigovernmental entities not supported by taxpayers.

Following the 1994 Northridge earthquake, the market for earthquake insurance in California collapsed as private insurers stopped writing coverage.

The California legislature responded in 1996 by creating a quasi-public entity, the California Earthquake Authority (CEA), to provide earthquake insurance to Californians. The CEA is not a government agency but operates under constraints mandated by the legislature.

Specifically, the policies written by the CEA are earthquake “mini-policies” designed by the legislature that provide less-extensive coverage than provided by private insurers pre-Northridge.

The legislature also mandated that coverage be provided at sound actuarial prices, although these have been “tempered” somewhat to subsidize policyholders in high-risk areas.

The legislature also required that the CEA be funded by capital contributions of about $700 million from private insurers licensed in California in lieu of requiring them to write earthquake insurance.

The CEA had claims-paying ability of about $6.9 billion at the end of 2004 (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2005). Putting this in perspective, recall that the Northridge earthquake caused insured losses of $18.5 billion (Table 1).

However, because of the mini-policies and because fewer residences have earthquake insurance now than before 1994, it is probable that the CEA could withstand damages on the scale of Northridge. Since the creation of the CEA, private insurers have re-entered the California earthquake market. In 2004, approximately 150 companies wrote nonzero earthquake insurance premiums in California (California Department of Insurance, 2005).

Of the $985 million in California earthquake premiums written in 2004, however, the CEA accounted for 47.3 percent; and private insurers generally write insurance in relatively low-risk areas of the state (Jaffee, 2005).

Nevertheless, the design of the CEA, and especially its mandate to charge actuarially justified premium rates, has had the effect of not crowding-out the private sector.

Something of a puzzle in the California market, however, is that only a small proportion of eligible property owners actually purchase the insurance. In the homeowners market, 33 percent of eligible properties purchased earthquake insurance in 1996, the CEA’s first year, but only 13.6 percent had insurance in 2003.

The rationale usually given for the low market penetration is that most buyers consider the price of insurance too high for the coverage provided, even though premiums are close to the expected losses (Jaffee, 2005).

As in California following Northridge, the hurricane market in Florida was significantly destabilized by Hurricane Andrew in 1992.23 In response to insurer attempts to withdraw and reprice windstorm coverage following the event, the state placed restrictions on the ability of insurers to decline renewal of policies and to increase rates.

To provide an escape valve for policyholders who were unable to obtain coverage, the state created the Florida Residential Property and Casualty Joint Underwriting Association (FRPCJUA), a residual market facility.

Insurers doing business in the state were required to be members of the facility, which insured people and businesses who could not obtain property coverage from the voluntary insurance market. The FRPCJUA was empowered to assess insurers if premiums were not sufficient to pay claims, and there was no explicit government backing.

A similar residual market facility was formed to provide “wind only” coverage along the coast— the Florida Windstorm Underwriting Association. In 2002, the two residual market plans were merged to form the Citizens Property Insurance Corporation, a tax-exempt entity that provides coverage to Floridian consumers and businesses who cannot find coverage in the voluntary market.

Citizens operates like an insurance company in charging premiums, issuing policies, and paying claims. If premiums are insufficient, it has the authority to assess insurers doing business in the state to cover the shortfall. It also has the ability to issue tax-exempt bonds if necessary.

Citizens was severely stressed by the four hurricanes that hit Florida in 2004, as it struggled to handle the massive numbers of claims that were filed. In 2004, Citizens wrote $1.4 billion in premiums, accounting for 34 percent of the Florida property insurance market.

Unlike California earthquake insurance, the market penetration of property insurance coverage in Florida is very high, in part because mortgage lenders require mortgagors to purchase insurance.

To provide additional claims-paying capacity, Florida also created the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund (FHCF), a state-run catastrophe reinsurance fund designed to assist insurers writing property insurance in Florida.

Insurers writing residential and commercial property insurance in the state are required to purchase reinsurance from the FHCF based on their exposure to hurricane losses in the state. The FHCF does not have state financial backing.

However, it is operated as a state agency and is exempt from federal income taxes, enabling it to accumulate funds more rapidly than private insurers. In addition, the fund has the authority to assess member insurers within limits in case premiums and reserve funds are insufficient and also has the ability to issue taxexempt bonds.

The catastrophe reinsurance issued by the fund kicks in after an industry retention of $4.5 billion, and the fund has claims-paying ability of about $15 billion. The FHCF helped to stabilize the property insurance market following the 2004 hurricane season and Hurricane Wilma in 2005.

The California and Florida experience shows that government can play an important role in making insurance available without directly committing taxpayer funding.

These programs also have the virtue of not crowding-out private insurers, although it is possible that the mandatory purchase feature of the FHCF may have crowdedout some private reinsurance.

However, because these are government-mandated and -designed programs, they probably are not as efficient as purely private market solutions.

Terrorism Insurance

Prior to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, terrorism was generally covered by most property-casualty insurance policies. In fact, the risk was considered so minimal by insurers that terrorism was usually included at no explicit price.

Likewise, reinsurers generally covered primary companies for terrorism as part of their reinsurance coverage; and reinsurers paid most of the claims resulting from the WTC attack.

After 9/11, however, reinsurers began writing terrorism exclusions into their policies, leaving primary insurers with virtually no opportunity to reinsure their exposure. As a result, the primary insurers sought to write terrorism exclusions into their own policies.

Recognizing that substantial exposure to terrorism risk without adequate reinsurance could pose insolvency risks, state insurance regulators rapidly approved terrorism exclusions.

By early 2002, insurance regulators in 45 states allowed insurers to exclude terrorism coverage from most of their commercial insurance policies.

In February 2002, the Government Accounting Office (GAO) gave congressional testimony providing “examples of large projects canceling or experiencing delays...with the lack of terrorism coverage being cited as the principal contributing factor” (Hillman, 2002, p. 9).

According to a survey by the Council of Insurance Agents and Brokers, in the first quarter of 2002, the market for propertycasualty insurance experienced “sharply higher premiums, higher deductibles, lower limits and restricted capacity from coast to coast and across the major lines of commercial insurance.

”25 In November 2002, Congress responded to these problems by passing TRIA. Through TRIA, the federal government required property-casualty insurers to offer or “make available” terrorism insurance to commercial insurance customers and created a federal reinsurance backstop for terrorism claims.

TRIA established the Terrorism Insurance Program within the Department of the Treasury. The program, which has been extended through December 31, 2007, covers commercial propertycasualty insurance—all insurers operating in the United States are required to participate.

Insurers are required to “make available property and casualty insurance coverage for insured losses that does not differ materially from the terms, amounts, and other coverage limitations applicable to losses arising from events other than terrorism” (U.S. Congress, 2002, p. 7).

The legislation thus nullified state terrorism exclusions and requires that insurers offer terrorism coverage. The wording of the Act implicitly omits coverage of chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) haz ards, which are not covered by most commercial property-casualty policies.

For the federal government to provide payment under TRIA, the Secretary of the Treasury must certify that a loss was due to an act of terrorism, defined as a violent act or an act that is dangerous to human life, property, or infrastructure, and to have “been committed by an individual or individuals acting on behalf of any foreign person or foreign interest, as part of an effort to coerce the civilian population of the United States or to influence the policy…of the United States Government by coercion” (U.S. Congress, 2002, p. 3).

Acts of war are excluded, and losses from any terrorist act must exceed a specified monetary threshold before the Act takes effect. The threshold was originally $5 million, increasing to $50 million in 2006 and $100 million in 2007.

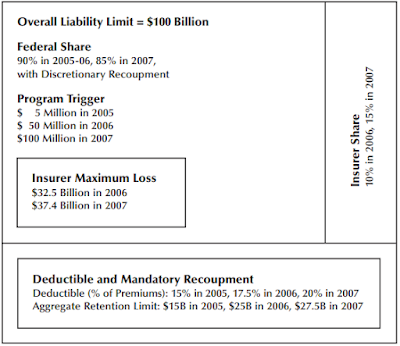

If a loss meets these requirements, the loss is shared by the insurance industry and the federal government under the deductible, copayment, and recoupment provisions of the Act. The coverage structure of the Act is diagramed in Figure 15.

In 2005, each individual insurer had a terrorism insurance deductible of 15 percent of its direct earned premiums from the prior calendar year, which increases to 17.5 percent in 2006 and 20 percent in 2007. Above the deductible, the federal government pays for 90 percent of all insured losses in 2005-06, decreasing to 85 percent in 2007.

However, the law provides for mandatory recoupment of the federal share of losses up to the level of the “insurance marketplace aggregate retention,” which is $15 billion in 2005, $25 billion in 2006, and $27.5 billion in 2007.

This recoupment is to occur through premium surcharges on property-casualty insurance policies in force after the event, with a maximum surcharge of 3 percent of premiums per year.

In addition, the Secretary of the Treasury has the discretion to demand additional recoupment, taking into account the cost to taxpayers, the economic conditions of the commercial marketplace, and other factors.

In other words, the Secretary of the Treasury could choose to recoup 100 percent of federal outlays under this program through ex post premium surcharges. The total, combined liability of the government and private insurers is capped at $100 billion.

In both 2006 and 2007, insurers are exposed to potentially large losses under TRIA. As shown in Figure 15, the deductible and recoupment provisions expose insurers to possible losses as high as $32.5 billion in 2006 and $37.4 billion in 2007.

Although these losses would be large by historical standards, they are of the same order of magnitude as the losses from the World Trade Center and Katrina, which the industry was able to absorb. In addition, the analysis of Cummins, Doherty, and Lo (2002) suggests that the industry could sustain losses of this magnitude without destabilizing insurance markets.

Government Catastrophe Insurance in Other Countries

This section provides a brief overview of the government role in catastrophe insurance in other countries based on OECD (2005a,b), GAO (2005), and other sources. Natural disaster programs are discussed first, followed by terrorism.

In many OECD countries, governments use tax revenues to establish prefunded disaster-relief funds. This approach is used in countries such as Australia, Denmark, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, and Poland (Freeman and Scott, 2005).

In several of these countries, the government provides compensation only for losses that cannot be privately insured. This approach is somewhat similar to the disaster-relief funding provided by the federal government in the United States.

Several countries have established government insurance programs to provide coverage for natural disasters. The government collects premiums in return for the coverage, and private insurers generally market the policies and handle claims settlement and other administrative details.

An example is Consorcio de Compensacion de Seguros (CCS), which was established by the Spanish government in 1954. CCS is a public corporation that provides insurance for “extraordinary risks,” including both natural catastrophes and terrorism.

The extraordinary risks coverage is mandatory and is provided as an add-on to private market property insurance policies. A premium is collected for the coverage, which is passed along to CCS by the private insurers.

Another approach, somewhat similar to TRIA, is for the government to act as a reinsurer rather than a primary insurer as it does in Spain. An example is France, which has two programs, the National Disaster Compensation Scheme and Fonds National de Garantie des Calamites Agricoles.

The former is backed by a stateguaranteed public reinsurance program, Caisse Centrale de Reassurance (CCR), which provides unlimited government backing for catastrophe losses. Catastrophe insurance is mandatory for all private non-life insurance policies.

Insurers can then reinsure the risk with CCR, which essentially serves as reinsurer of last resort. Premium surcharges for the catastrophe insurance are set by the French government. Another example of the government as reinsurer is provided by the Japan Earthquake Reinsurance Company, which reinsures natural hazards such as earthquakes and tsunamis in Japan.

All earthquake insurance written by private insurers in Japan is reinsured with the Japan Earthquake Reinsurance Company.

Reinsurance coverage is based on a layering approach, such that 100 percent of the loss in the lowest-loss layer, up to 75 billion yen, is borne by private insurers; the loss is split evenly between private insurers and the government when the loss is between 75 billion and 1.0774 trillion yen; and 95 percent of the loss is paid by the government when the loss is between 1.0774 and 4.5 billion yen (Freeman and Scott, 2005).

According to the OECD (2005b), there are government terrorism insurance programs in eight OECD countries: Australia, Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

All of the programs were established after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks except for the Spanish program, where coverage is provided by CCS, and the U.K. program, which was established in 1993 in response to Irish Republican Army terrorist attacks.

The programs vary along several important dimensions, including coverage layers and amounts, the limitations on the liability of private insurers, whether a premium is charged for the government reinsurance, and whether the plan is temporary or permanent. In the following, I give examples based on the most prominent plans rather than providing a comprehensive analysis.

In December 2001, a new reinsurer called Gestion de l’Assurance et de la Reassurance des Risques Attentats et Actes de Terrorisme (GAREAT) was established in France to reinsure terrorism risk insurance written by private insurers.

The French government acts as reinsurer of last resort, providing unlimited reinsurance coverage through CCR. As is common in conventional catastrophe reinsurance, government terrorism reinsurance coverage is provided in a sequence of layers.

The first layer of 400 million euros of coverage is provided by the private insurers who participate in GAREAT.

As of 2005, there are two layers of private market reinsurance: The first layer provides limits of 1.2 billion euros in excess of the 400 million euro primary layer, and the second layer provides 400 million euros in excess of 1.6 billion euros.

Above 2 billion euros, unlimited coverage backed by a government guarantee is provided by CCR. As with other catastrophe insurance in France, terrorism coverage is mandatory for all property insurance. A premium is collected for the government reinsurance, which is remitted to the government.

GAREAT is set to expire at the end of 2006 (Michel-Kerjan and Pedell, 2005). In Spain, terrorism insurance is provided under the CCS program. Therefore, it is mandatory for all non-life insurance. There is no layering.

All extraordinary risks coverage is ceded to CCS, which is backed by an unlimited government guarantee. Policyholders pay a premium surcharge for the coverage provided by CCS, including terrorism coverage.

The program is permanent. In Germany, a specialist insurer, EXTREMUS, was established in 2002 to provide terrorism insurance. The program is set to terminate at the end of 2007. Coverage is not mandatory in Germany, and demand for terrorism insurance is reportedly very low.

The first 2 billion euros of coverage is provided by private insurers and reinsurers, and there is excess reinsurance coverage (8 billion euros in excess of 2 billion euros) provided by the German government in return for a premium.

The annual maximum indemnity for each client is limited to 1.5 billion euros. In the United Kingdom, a mutual reinsurance company, Pool Re, was established in 1993 to provide terrorism reinsurance to insurers writing insurance in the United Kingdom.

Pool Re has a retrocession arrangement with the British Treasury to provide the ultimate layer of reinsurance. The first layer of coverage is provided by primary insurers, up to 75 million pounds per event or 150 million pounds per year (in 2005), industrywide.

Coverage is then provided by Pool Re up to the full amount of its resources. Coverage for events that exhaust the funds in Pool Re is provided by the government in return for a premium.

Among the eight OECD terrorism programs covered in OECD (2005b), only Austria’s does not involve some form of government insurance. Among the seven programs with government backing, five are temporary and four have fixed expiration dates.

Government reinsurance is unlimited in France, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Among the countries with limits on the liability of the government reinsurance, the highest limit is in the U.S. TRIA program.

Among the programs with government backing, only the U.S. program does not charge a premium for the reinsurance, although the Secretary of the Treasury has the authority to seek recoupment of losses exceeding the industry participation limits.

The lack of a premium is a defect in the U.S. program because it has the effect of crowding-out private reinsurers, who cannot compete with free coverage.

Posting Komentar untuk "Government Involvement in Catastrophe Insurance Markets"