Target loans, current account balances and capital flows

This paper investigates the Target balances, an accounting system hidden in remote corners of the balance sheets of the Eurozone’s National Central Banks (NCBs), to analyze the Eurozone’s internal imbalances.

It presents the first comprehensive Target database by collecting and reconstructing information from the NCB balance sheets and IMF statistics, a method subsequently also adopted by the ECB itself, and shows that the Target surpluses and deficits basically have to be understood as classical balance-of-payments surpluses and deficits as known from fixed-exchangerate systems.

To finance the balance-of-payments deficits, the European Central Bank (ECB) tolerated and actively supported voluminous money creation and lending by the NCBs of the periphery at the expense of money creation and lending in the core of the Eurozone.

This has shifted the Eurozone’s stock of net refinancing credit from the core to the periphery and has converted the NCBs of the core into net debtors of their banking systems, institutions that mainly borrow and destroy euro currency rather than print and lend it.

The reallocation of refinancing credit was a public capital flow through the ECB system that helped the crisis countries in the same sense as the official capital flows through the formal euro rescue facilities (EFSF, EFSM and the like) did, but it actually came much earlier, bypassing the European parliaments. It was a rescue program that predated the rescue programs.

As we will show, by replacing stalling capital imports and outright capital flight, Target credit financed substantial portions, if not most, of the current account deficits of Greece and Portugal during the first three years of the crisis, and a sizeable fraction of the Spanish current account deficit.

In the case of Ireland, they financed a huge capital flight in addition to the country’s current account deficit. Beginning with the summer of 2011, they have financed an even more vigorous capital flight from Italy and Spain.

With the Italian capital flight, the Target credits have reached a new dimension and the ECB has entered a new regime, whose implications for the survival of the Eurozone should be discussed by economists. We can only touch upon the upcoming issues in this introductory piece.

Target loans through the Eurosystem

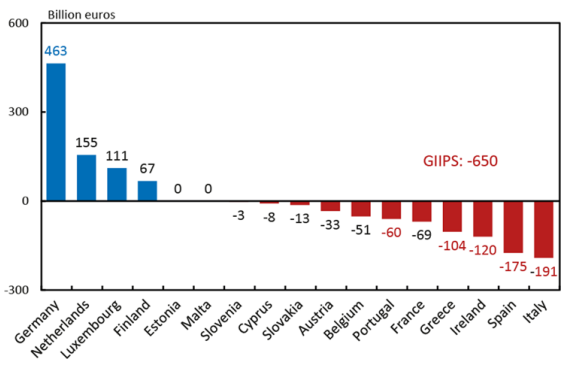

The Target claims and liabilities that had accumulated in the NCBs’ balance sheets until December 2011 are shown in Fig. 1. Germany, by that time, had claims on the Eurosystem amounting to 463 billion euros, and the GIIPS (Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain) in turn had accumulated a liability of 650 billion euros. The Target liabilities of Ireland and Greece alone amounted to 120 and 104 billion euros, respectively.

The Target claims and liabilities are interest-bearing. Their interest rate equals the ECB’s main refinancing rate. However, interest revenues and expenses are socialized within the Eurosystem.

The Target liabilities constitute net foreign debt and, as such, they enter (negatively) into a country’s net foreign asset position. By the end of 2011, for Greece this debt amounted to 48 % of GDP, for Ireland to 77 %, for Italy to 12 %, for Portugal to 35 %, and for Spain to 16 %.

The Target imbalances went unnoticed for a long time because they are not shown on the ECB’s balance sheet, given that they net out to zero within the Eurosystem. They can be found, however, if somewhat laboriously, in the NCBs’ balance sheets under the “Intra-Eurosystem Claims and Liabilities” position.

Furthermore, they can be found in the balance-of-payments statistics, where they are shown as a flow in the financial account under the “Other Financial Transactions with Non-residents” position of the respective NCBs and as a stock labelled “Assets/Liabilities within the Eurosystem” in the external position of the respective NCBs.

Interestingly enough, the ECB revealed in October 2011, in its first publication on the issue, that it does not possess a reporting system of its own, but constructed the missing data from the IMF statistics, thus following the method we had introduced in the June 2011 version of this paper.

The details are spelled out in the appendix to this paper. Many think that the Target imbalances are a normal side effect of the Eurozone payment system, as they are wont to occur in a currency system. This assessment is contradicted, however, by the dramatic evolution shown in Fig. 2, which, as we will show below, in all likelihood would not have been possible in the US system.

The Target imbalances evidently started to grow by mid-2007, when the interbank market in Europe first seized up. Before that they were close to zero. German claims, for instance, which by April 2012 had climbed to 644 billion euros, amounted to barely 5 billion euros at the end of 2006.

It is striking that a strong, albeit not perfect, coincidence exists between the rise of the German Target claims and the rise in the Target liabilities of the GIPS (Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain). Other countries were involved, but with smaller amounts, as shown in Fig. 1.

The creditor countries included Luxembourg, Finland and the Netherlands, while the debtors included Austria, France, Belgium and Slovakia, and, in particular, Italy. But the key players are, evidently, the GIPS, Italy and Germany.

During the first three years of the crisis Italy was not involved. Figure 2 shows Italy among the countries having a Target claim until June 2011.

However, from July 2011 on, when markets turned jittery about Italy, forcing the Berlusconi government to enact austerity measures, the country also became a Target debtor.

The Target balance of the Bank of Italy fell by 197 billion euros in only six months, from +6 billion euros in June 2011 to −191 billion euros by the end of 2011, of which −87 billion euros were accumulated in August and September alone.

By April 2012 the Italian Target debt had rocketed to 279 billion euros. Interestingly enough, the rise in the Italian Target debt coincides with the sudden rise of the Dutch Target claim since the summer of 2011.

By the end of 2011, the volume of Target credit drawn by the GIIPS (GIPS plus Italy) from the ECB system was 650 billion euros. It far exceeded the 172 billion euros in official aid given or promised to them by all the Eurozone countries combined.

The official Bundesbank and ECB statements

After one of us brought the Target imbalances to public attention, the Bundesbank and later the ECB reacted with various, nearly identical statements.5 In essence, both institutions said:

- The Target balances are statistical items of no consequence, since they net each other out within the Eurozone (Bundesbank).

- Germany’s risk does not reside in the Bundesbank’s claims, but in the liabilities of the deficit countries. Germany is liable only in proportion to its share in the ECB, and if it had been other countries instead of Germany that had accumulated Target claims, Germany would be liable for exactly the same amount (Bundesbank and ECB).

- The balances do not represent any risks in addition to those arising from the refinancing operations (Bundesbank and ECB).

- A positive Target balance does not imply constraints in the supply of credit to the respective economy, but is a sign of the availability of ample bank liquidity (ECB).

All points are basically correct (and do not contradict what we said in previous writings), but they hide the problems rather than clarify them and deny the fundamental distortions in the euro countries’ balances of payments which, as we will argue, are precisely measured by the Target balances.

Point 1 is true, but irrelevant. Between a debtor and its creditor the balances net out to zero, but that does not make the creditor feel at ease if he doubts the debtor’s ability to repay. Point 2 is true if a country defaults and exits the euro, while the Eurosystem as such survives.

In this case, the Eurosystem is legally disconnected from the commercial banks of the defaulting country, while its Target claim against this country’s NCB remains. If this claim cannot be serviced, the corresponding write-off loss is shared by all remaining NCBs in the Eurosystem according to their capital shares.

Should the disaster hit all GIIPS, Germany, for example, would be liable in proportion to its (enhanced) capital share in the ECB, namely about 43 % of the 650 billion euros in GIIPS liabilities (by the end of 2011), i.e. around 277 billion euros. Similarly, France would have to bear 32 %, or 208 billion euros. However, if Italy and Spain defaulted, this could mean the end of the Eurosystem.

In this case, it cannot be taken for granted that the former members of the euro community would be willing to participate in sharing the write-off losses of the creditor countries. Legally, this is a gray area, and here the Bundesbank and the ECB are wrong, as the Bundesbank and the other NCBs with a positive Target balance would have claims against a system that no longer exists.

Point 3 is true, but misleading, as it hides the unusual size of the liability risk implied by the Target credit, even if no country defaults.

To be sure, this credit materializes through the Eurosystem’s refinancing operations (including emergency loans, socalled Emergency Liquidity Assistance, ELA, guaranteed by the respective sovereign that some NCBs granted on their own against no or only insufficient collateral).

But it does measure, as we will show below, the additional refinancing credit an NCB issues to finance the country’s balance-of-payment deficit with other Eurozone countries. As such it does imply more risk than in the case where the refinancing credit had been limited to the provision of a country’s own money circulation.

Point 3 is as true and meaningful as the statement that the crash of a Jumbo jet does not involve any risk beyond that of the mere crash of an airplane. Point 4, finally, is true, insofar as a positive Target balance signals generous liquidity provision in a country.

But, as we will show in Sect. 7, it is precisely this abundance of liquidity that implies a crowding-out of refinancing credit in Germany. The Target imbalances do measure an international capital export through the Eurosystem, and hence a public credit, mainly from Germany, to the GIIPS.

This is not a net outflow of credit, private inflows and public outflows taken together, but in itself it is an outflow in the same sense as a public rescue credit from one country to another is such an outflow.

Posting Komentar untuk "Target loans, current account balances and capital flows"